Hva er greia med løk og kadmium?

EU-forordning skaper problemer for løkbønder rundt Mjøsa.

The text is an abbreviated excerpt from the report, A Legal View of the Free Trade Alternative to the EEA Agreement (University of Tromsø 2014), and has also been published in Vett 1-2015 .

Some would say that copying Switzerland’s agreements with the EU is unrealistic. The Europe Report states, for example, that ‘the EU has increasingly expressed dissatisfaction with how the agreements function. In the Council’s assessments from 2010, the EU noted that the cooperation with Switzerland creates legal uncertainty and is difficult to manage, and that this form of cooperation has "clearly reached its limits."’1 This negative attitude towards the agreements with Switzerland is also apparent in the European Parliament: ‘In general, [...] the EEA Agreement works well.’ At the same time, the parliament takes the opportunity to assert that the EEA Agreement stands in sharp contrast to the type of agreement the EU has chosen with Switzerland. 2 This has led the EU and Switzerland's Federal Council to propose a Framework Agreement in connection with the trade agreements.

The Framework Agreement aims to unravel the tangled knots of the agreements’ institutional aspects. While the general perception in Switzerland seems to be that the country was willing to let the European Court have the final word in interpreting the bilateral free trade agreements, this is officially rejected. It is the Swiss courts that shall interpret the country's international law obligations in relation to the Free Trade Agreement with the EU. It is only in cases where there is disagreement between the EU and Switzerland that the EU's interpretation will prevail. This is a compromise proposal in what is characterised as a deadlocked situation. The proposal has met strong criticism in Switzerland. It is argued that Switzerland has acceded to the EU’s demands in a way that strongly reduces Switzerland's sovereignty.

In the interest of both partiesWe cannot just assume that the EU will want to include Norway on a par with Switzerland in a much extended free trade agreement. The answer to this question lies in the darkness of the future. But the EU has a big deficit in its production of fish and oil/gas. This is to a large extent covered by imports from Norway. Norway's position when it comes to the supply of fresh seafood and oil/gas through pipelines means that the EU is at least as dependent on

The figures speak for themselves. As shown in the Europe Report, Norway has grown steadily as an export market for the EU: ‘The development of individual product groups shows that the share of processed industrial products of total exports to the EU has fallen from around 34 per cent in 2001 to under 30 per cent in 2010.’ In contrast, imports from the EU have increased significantly: ‘The value of imports of commodities from the EU to Norway has increased by 250 per cent since 1992.’ The European Union will lose out if the EEA Agreement is not replaced by a free trade solution. This suggests that both parties, and particularly the EU, have a strong interest in developing free trade.

Since the relationship with Switzerland is well-regulated by the Free Trade Agreement (1972) and the 18 additional agreements, the work involved in agreeing similar arrangements with Norway would not be particularly demanding. And to the objection that Paal Frisvold, the former leader of Norway's Europabevegelsen (European Movement), puts forward that ‘it is unlikely that the EU will agree to create a separate regulatory regime for EEA countries beside the EU’, the following can be said: A free trade solution of the Swiss type already exists. If Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein withdraw from the EEA Agreement, then this will therefore be the platform that the EU and the EFTA countries will have to fall back on. It will be easy to convert all the ‘Joint Committees’ into an EU-EFTA Committee with the same responsibilities as before. The only difference will be that the EFTA countries must agree common standpoints among themselves before the meetings of the committee. For the EU, the situation will be exactly as before. This is – as far as this report's authors can judge – not unrealistic.

The EU is unlikely to refuse to make a deal similar to the one with Switzerland since Norway and the EU already are bound by the Free Trade Agreement of 1973. With some simple adjustments, the agreements the EU and Switzerland have developed can be expanded to include Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway. It is also advantageous for a free trade solution that the EU and Ukraine recently signed a free trade agreement, that the EU has negotiated an agreement with Canada (CETA) and that the EU is negotiating with the United States on a free trade agreement (Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership). In none of these cases was there talk of linking the USA, Canada or Ukraine to the EEA Agreement. Obvious solutions in the above-mentioned direction cannot be impossible when it comes to Norway, which already has a free trade agreement.

The EU and Switzerland signed a principal agreement on free trade (1972) with a total of 18 auxiliary agreements, the latter as substitutes for the EEA Agreement, which Switzerland was originally a part of (the Oporto Agreement of 2 May 1992), but which was scuppered by a referendum on 6 December 1992. Some of the agreements are ‘horizontal’, i.e. they cover all or most sectors of trade relations.

This applies to the Free Trade Agreement (1972) and the Agreement on Conformity Assessments.

The 18 auxiliary agreements are based on the free trade agreement that the EEC and Switzerland signed on 22 July 1972, ‘ the Agreement between the European Economic Community and the Swiss Confederation.’6 It aims to abolish tax, tariff and quantitative barriers to trade in industrial products between the EU and Switzerland. The agreement contains a total of five appendices and a Final Act, plus joint and unilateral declarations. The appendices contain rules for preferential treatment of certain groups of products, specific rules on cost compensation for particularly difficult production conditions in agriculture, rules of origin and administrative cooperation. There are special provisions concerning Ireland's relationship with Switzerland and for Swiss stockpiles of products in the event of war or emergency situations. It is worth noting that, for several group of agreements, it is a requirement that all of the agreements in the group (often seven agreements) must enter into force. If one of them is not ratified, they are all affected.7

The principle underlying trade law is general international law: nation states are sovereign. This means that states themselves decide whether or not. and to what extent, they want to bind themselves internationally.

The obligation to incorporate the EU's legal arrangements goes no further than what agreed in the trade agreement and its auxiliary agreements. This is also the most important consequence of the sovereignty principle: All ‘residual rights’ rest with the sovereign state. That is to say that competence that has not been positively transferred to others still belongs to the nation state. This can be illustrated by a few examples: the main trade agreement and the 18 auxiliary agreements cover areas that have been specified. In general, trade in services is not included; the areas that are included are specifically mentioned. Swiss policy in areas that are not mentioned is not subject to limitations. Specifically, this means that, in relation to public procurements of goods and services and work in certain specified parts of the public sector, the trade agreement only concerns public procurements and only procurements relating to telecommunications; railways; energy; transport; extraction and distribution of coal; oil; gas; production, transportation or distribution of drinking water; electricity and services in the building sector. A few Swiss exceptions to the rules on tendering apply to the latter sector.

Public procurements of, for example, books for public schools, libraries and universities, military equipment. the rental or purchase of buildings for healthcare, hospitals, refugee centres, prisons etc., equipment for public buildings etc. all fall outside the scope of the agreement.

The agreement on trade relations and cooperation in fields other than trade, such as on fighting crime and asylum centres, only applies if and insofar as the agreement covers the field in question. Since the general presumption is that a country has a national right to adopt its own legislation, restrictions on sovereignty must be clearly expressed in the treaties.

The structure of the cooperation between the EU and Switzerland is such that the relationship is regulated through bilateral treaties between two peoples, i.e. a form of regulation that is based on the parties being equal. Neither the EU nor EU law takes precedence, and nor do EU votes carry more weight in decisions based on the agreement. Where joint committees are established, decisions are made unanimously. In connection with disputes and decisions that are referred to arbitration, each party appoints a judge, and the chairman of the court is chosen jointly by the two judges that have been appointed or, in cases where the two judges do not agree, by the International Court in The Hague.

The criticism of the newly negotiated Agreement is precisely that the equal status that the EU and Switzerland have in the free trade agreements has disappeared in the new Framework Agreement. The State Secretary Yves Rossier rejects this claim: ‘Switzerland will not submit to the European Court, but will only, when there is a difference of opinion with the EU, obtain the opinion of the European Court of Justice. Against this, these professors [who have signed a letter containing alternative proposals] argue for a model in which Switzerland – and only Switzerland – is subordinated, while the EU in no instance is subordinated.’ This means that, under the present regime, Switzerland can, veto the implementation of new EU regulations and directives, and that changes to the treaties cannot happen without Switzerland’s decision-making bodies, as authorised by the Constitution, accepting them. This also means that the principle is that the provisions of EU law do not have direct effect in Switzerland, neither for the state nor for individuals. In order for them to have such effect, the provisions must be transposed and implemented by Swiss national legislative bodies.

Unless otherwise specified in any of the 18 agreements between the EU and Switzerland, the power to adopt national legislation within the framework of the trade agreement (the 1972 Free Trade Agreement Article 10) is upheld, provided that it does not involve discrimination based on nationality (Article 15.2).

For the ‘free movement of persons’, the parties have agreed that the relationship is governed by EU rules cf. the Preamble. This is also the case for the Civil Aviation Agreement. This means that the parties operate in accordance with a harmonised legal order between Switzerland and the EU.

Changes that the EU makes to its regulations, and that, pursuant to the agreements between Switzerland and the EU, are intended to also apply in Switzerland, are submitted to Swiss experts on an equal footing with EU experts, who thus have a full right to raise objections and propose changes.

New court judgments and decisions that are made after the date on which the agreement was signed (21 June 1999) do not apply to Switzerland, not even in areas that are harmonised. New rules or judgments must be communicated to Switzerland, which then decides whether changes or court-created law is to be implemented in Swiss law.

Harmonised legislation is not part of most of the partial agreements; instead, laws are approved according to conformity assessments, i.e. both the EU and Switzerland continue to operate in accordance with their own rules. The various regulations are reviewed and subject to mutual recognition pursuant to the principles of international trade on conformity assessments (the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade, the Preamble).

Compliance reviews are also practised in connection with enforcement. The importing country must accept that the control that the exporting country undertakes is adequate with regard to requirements for necessary documentation, which confirms that the product is in compliance with the legal requirements of the importing country or equivalent requirements of the exporting country (Agreement on simplified customs control between the EU and Switzerland, Article 6).

Where Joint Committees are appointed, i.e. in a ‘two-pillar’ system, power of decision is shared, so that both Switzerland and the EU have a veto, because Switzerland and the EU both have seats on the committee and because all decisions are taken unanimously. Amendments to the agreements and their appendices adopted by the Joint Committee require national ratification in accordance with the home country's constitutional rules if they are to be binding (See Agreement on Agriculture for processed products Article 5).

The Joint Committee has monitoring functions, such as conformity assessments (for example, the Basic Agreement on Free Trade of 1972, Article 34) of administrative systems' correctness. According to the agreement, the countries must mutually recognise such systems as equal (Agreement on simplified customs control between the EU and Switzerland Articles 12.3 and 13). But the committee has no enforcement powers, neither in the EU nor Switzerland. If the Joint Committee cannot agree, and the parties wish to arrive at a solution, the mater is referred to an ‘arbitration tribunal’ or negotiations (the Insurance Agreement, Article 38).

There is a unilateral right to withdraw from the agreement. The agreement terminates either six or 12 months after the other party has been notified.

EU-forordning skaper problemer for løkbønder rundt Mjøsa.

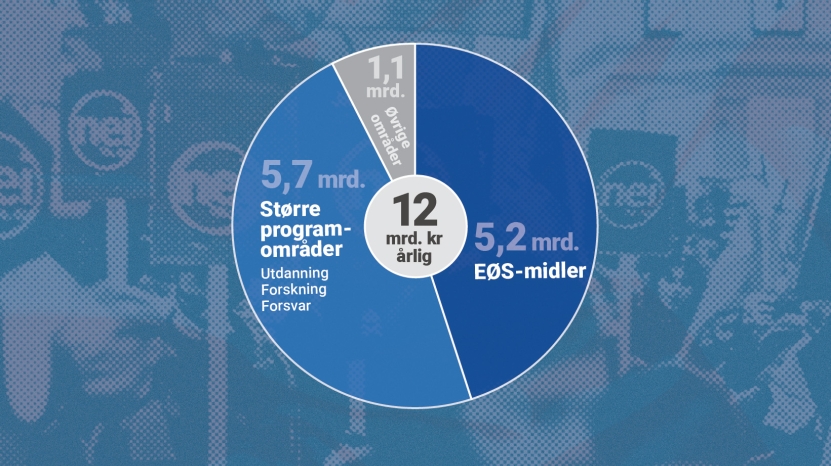

Alle nordmenn over 20 år må betale ca. kr 9000 i «EØS-avgift» fram til 2028.

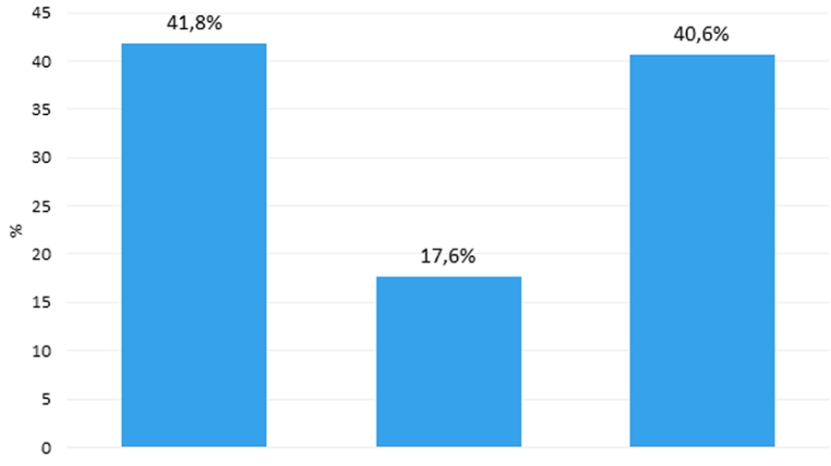

Bare 17,6 prosent av de spurte er mot at Norge melder seg ut av EUs energibyrå ACER, viser en ny meningsmåling.